Emily Lakdawalla • Sep 12, 2016

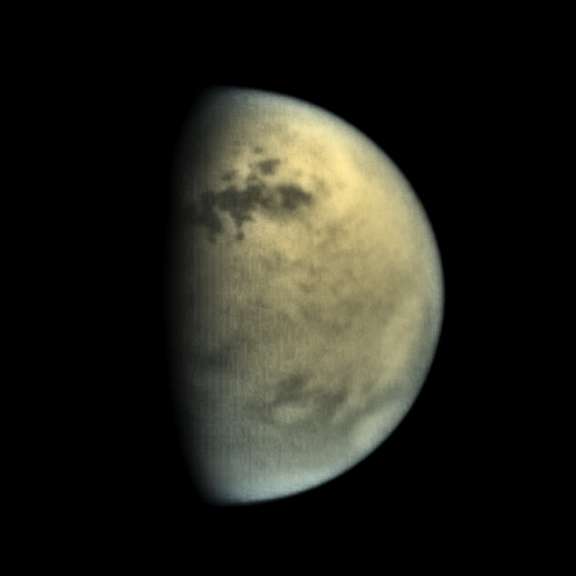

Cassini's camera views of Titan's polar lakes in summer, processed into pseudocolor

The Cassini Saturn orbiter first spotted lakes in Titan's northern polar region using its radar instrument very early in the mission. The lakes were initially invisible to Cassini's optical instruments, because when Cassini arrived it was winter at the north pole, so no sunlight ever reached them. Over its long, long mission Cassini has seen Saturn and Titan go through equinox, and now they are approaching northern summer solstice. That keeps the lake district in the sunlight for most of the Titan day, and also gives sunlight a shorter path through Titan's smoggy atmosphere to the north pole, making images clearer. Recently, image processing enthusiast Ian Regan has been working with Cassini photos, developing his own recipe for processing the fuzzy raw frames into crisp, colorful views.

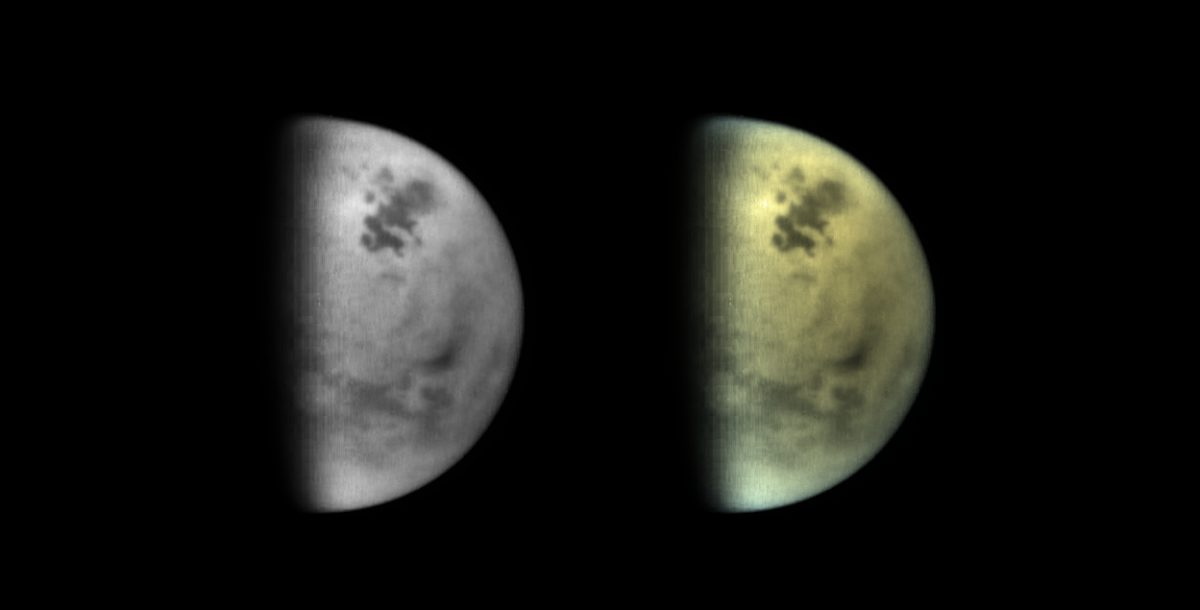

Here you can see Ian's efforts develop:

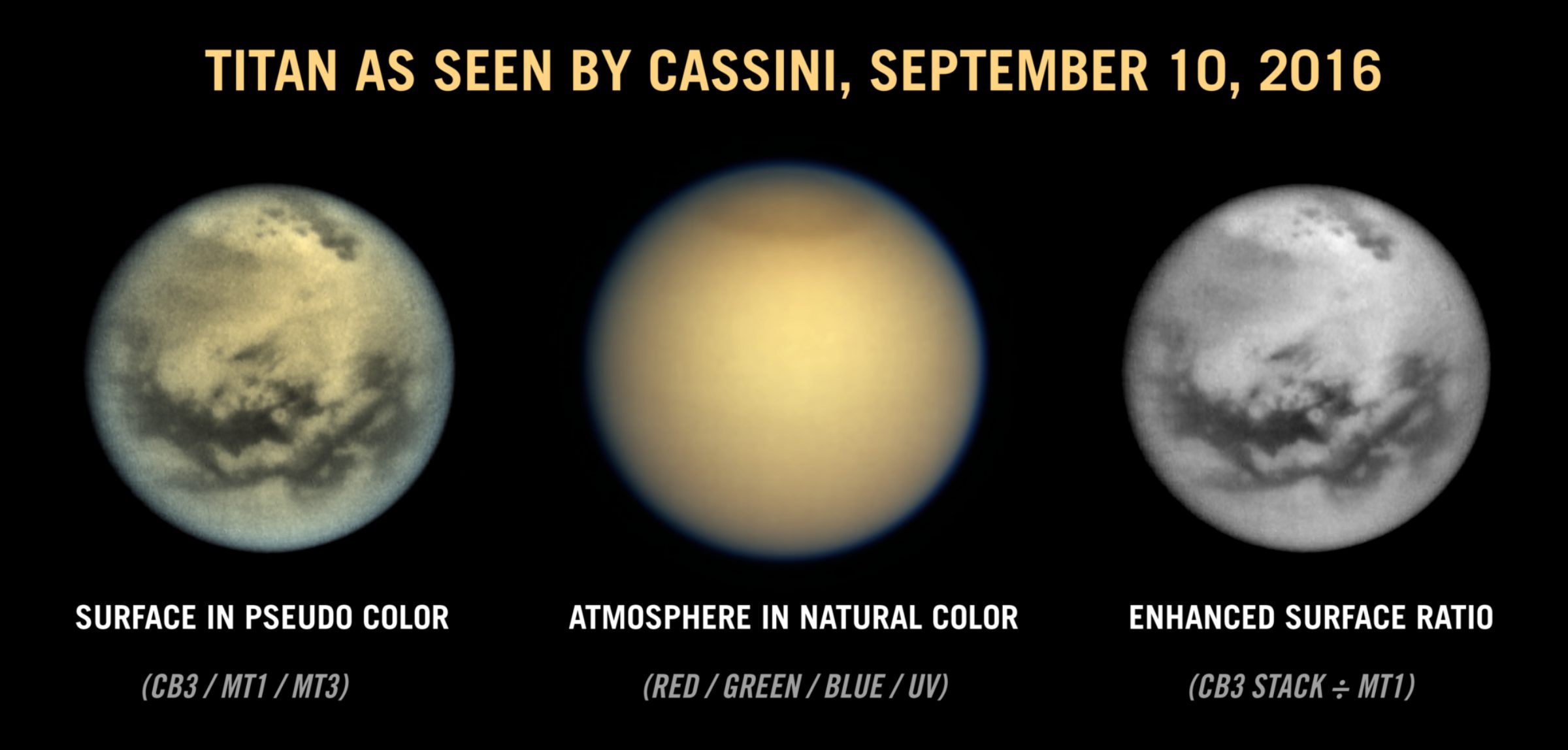

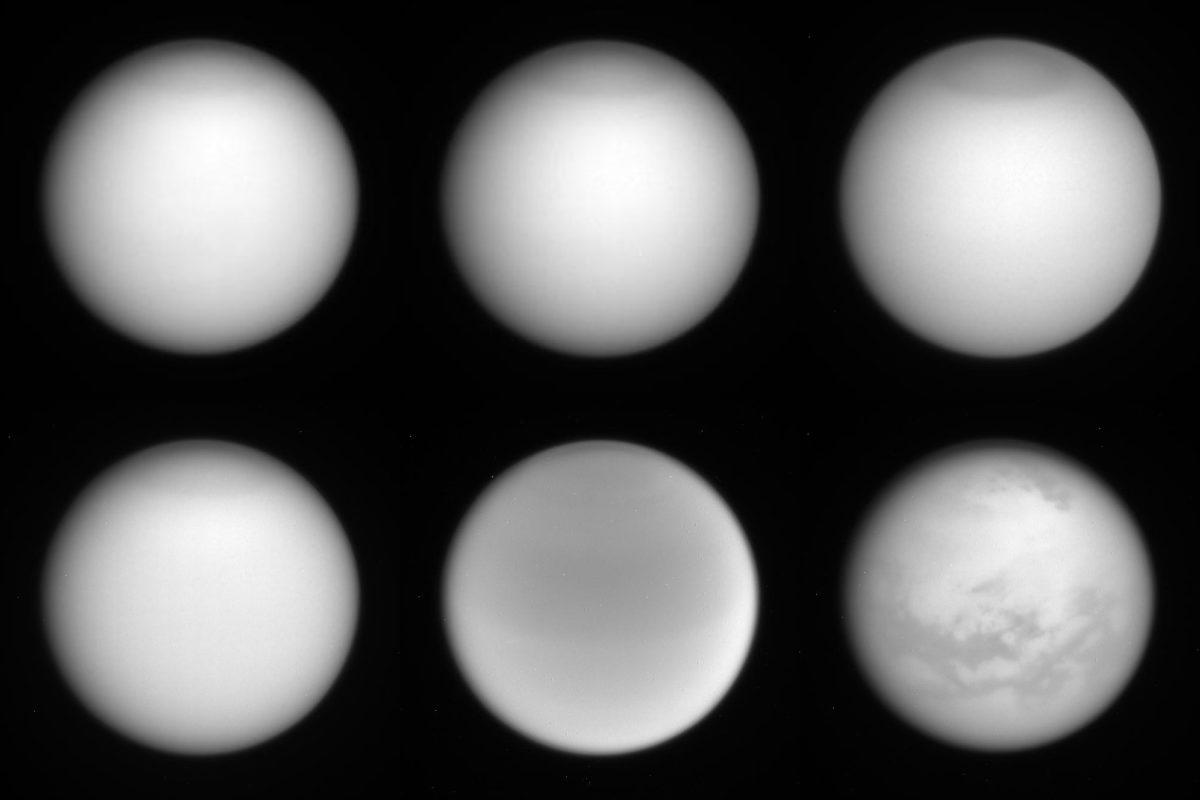

Ian kindly shared his recipe with me. He begins with raw Cassini images of Titan taken through infrared filters CB3, MT1, and MT3, common choices for Cassini Titan imaging. These filters block all but very narrow slices of the electromagnetic spectrum from reaching Cassini's camera detector. By rotating different filters in front of the camera, Cassini's scientists can study how Titan reflects sunlight at different wavelengths, see structures in the atmosphere and on the surface, and sometimes even detect compositional differences from place to place. MT1 and MT3 are in wavelengths where methane in Titan's atmosphere absorbs light (at about 620 and 850 nanometers). CB3 is at 950 nanometers, a wavelength in which methane is relatively transparent, so surface features become visible. Cassini usually takes several CB3 images in a single observation, which can be stacked to improve the signal.

Ian uses the free and open-source ImageJ for image manipulation, aided by the StackReg and Bio-Formats plugins. Following is the recipe he uses; it sounds like these tools could be useful for other image processing projects.

I thank Ian for sharing his notes. Want to see more of his work? Check out Ian's page in The Planetary Society's amateur image library, and see much more on Ian Regan's Flickr page.

Let’s Go Beyond The Horizon

Every success in space exploration is the result of the community of space enthusiasts, like you, who believe it is important. You can help usher in the next great era of space exploration with your gift today.

Donate Today

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth