Emily Lakdawalla • Nov 17, 2014

Rosetta imaged Philae during its descent -- and after its bounce

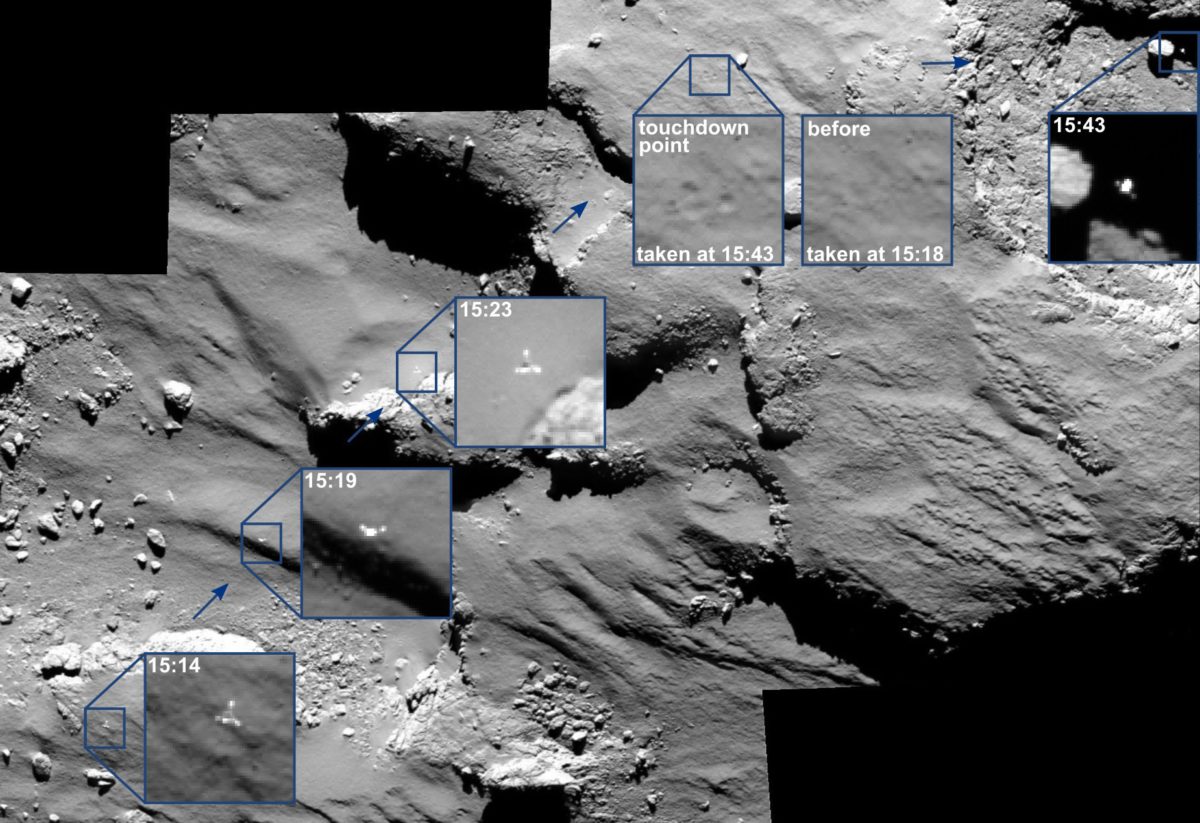

This morning ESA released a set of images of the Philae lander taken by the Rosetta orbiter during -- and after -- the lander's first touchdown. If the touchdown had happened nominally, one of these images would have shown Philae sitting on the surface. As it happens, the images contain evidence for the spot Philae first touched the comet, and a crucial photo of Philae's position several minutes into its first long bounce, showing that the lander took a sharp right turn after hitting the ground.

Let's just pause for a moment to appreciate how awesome that series of images is. Especially the final one in the sequence, taken at 15:53, showing the sunlit spacecraft silhouetted against a black shadowed cliff. The lander is headed off in a completely different direction than the one from which it approached -- at least from Rosetta's point of view. (From the comet's point of view, the lander was descending vertically, then bounced east.)

According to navigational data supplied to the Jet Propulsion Laboratory by the European Space Agency, here is some detailed information about the positions of lander and orbiter at the moments those pictures were taken. There is a full minute-by-minute table of altitude and position for both Philae and Rosetta calculated by Joe Knapp from SPICE navigational data available at unmannedspaceflight.com. Data for Philae ends at the moment of first touchdown, because they don't yet know Philae's post-impact trajectory. It shows Philae on the ground at an altitude of 158 meters, which must be measured relative to a reference ellipsoid for Churyumov-Gerasimenko.

| Date | Time | Philae altitude (km) | Sub-Philae Longitude | Sub-Philae Latitude | Rosetta Altitude (km) | Sub-Rosetta Longitude | Sub-Rosetta Latitude |

| 2014-11-12 | 15:14:00 | 1.337 | 149.62 | -27.28 | 15.179 | 174.19 | -27.54 |

| 2014-11-12 | 15:19:00 | 1.068 | 148.12 | -26.72 | 15.176 | 172.21 | -27.41 |

| 2014-11-12 | 15:23:00 | 0.848 | 147.05 | -26.18 | 15.175 | 170.63 | -27.30 |

| 2014-11-12 | 15:35:00 | 0.158 | 144.82 | -23.44 | 15.181 | 165.90 | -26.96 |

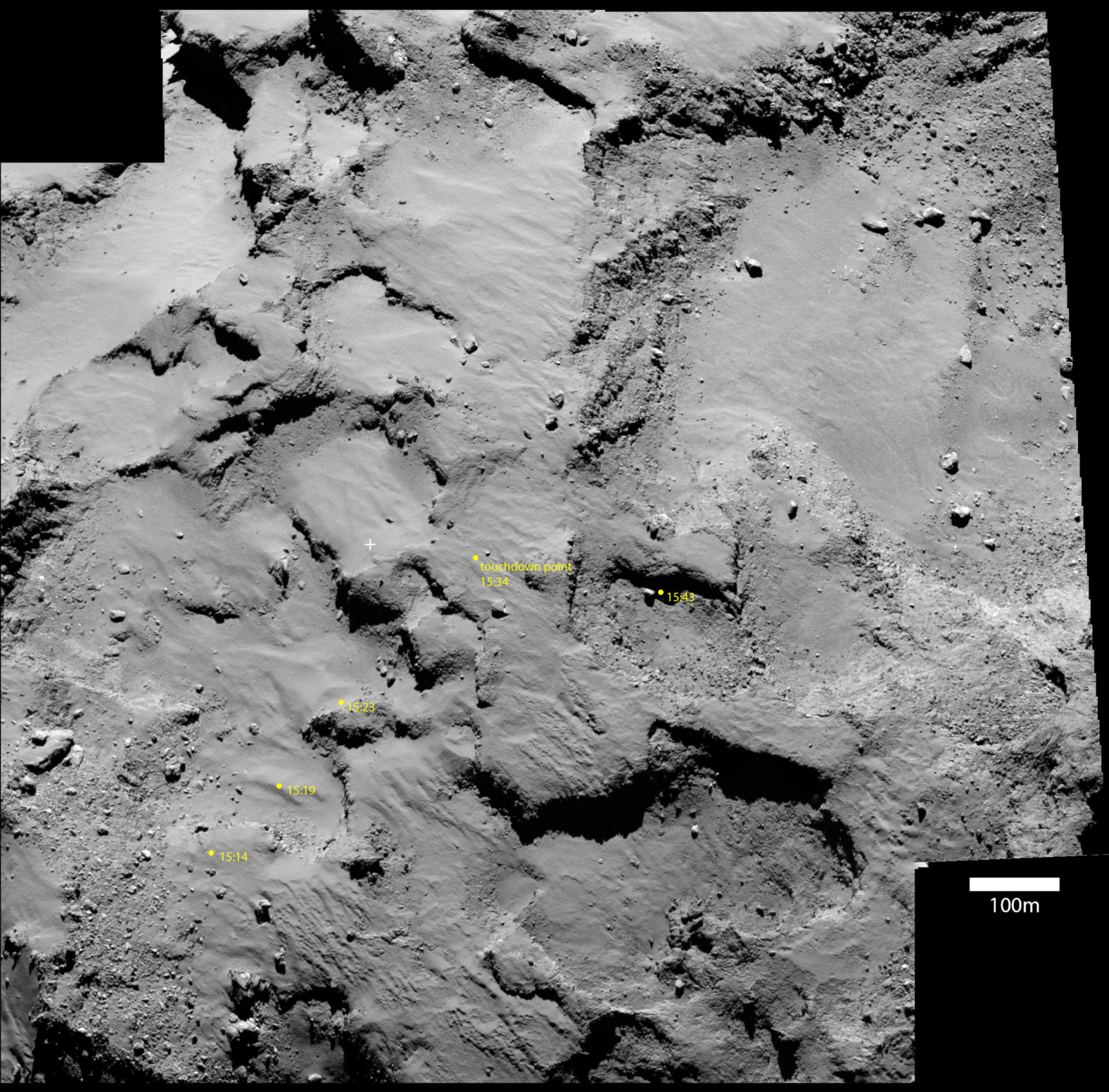

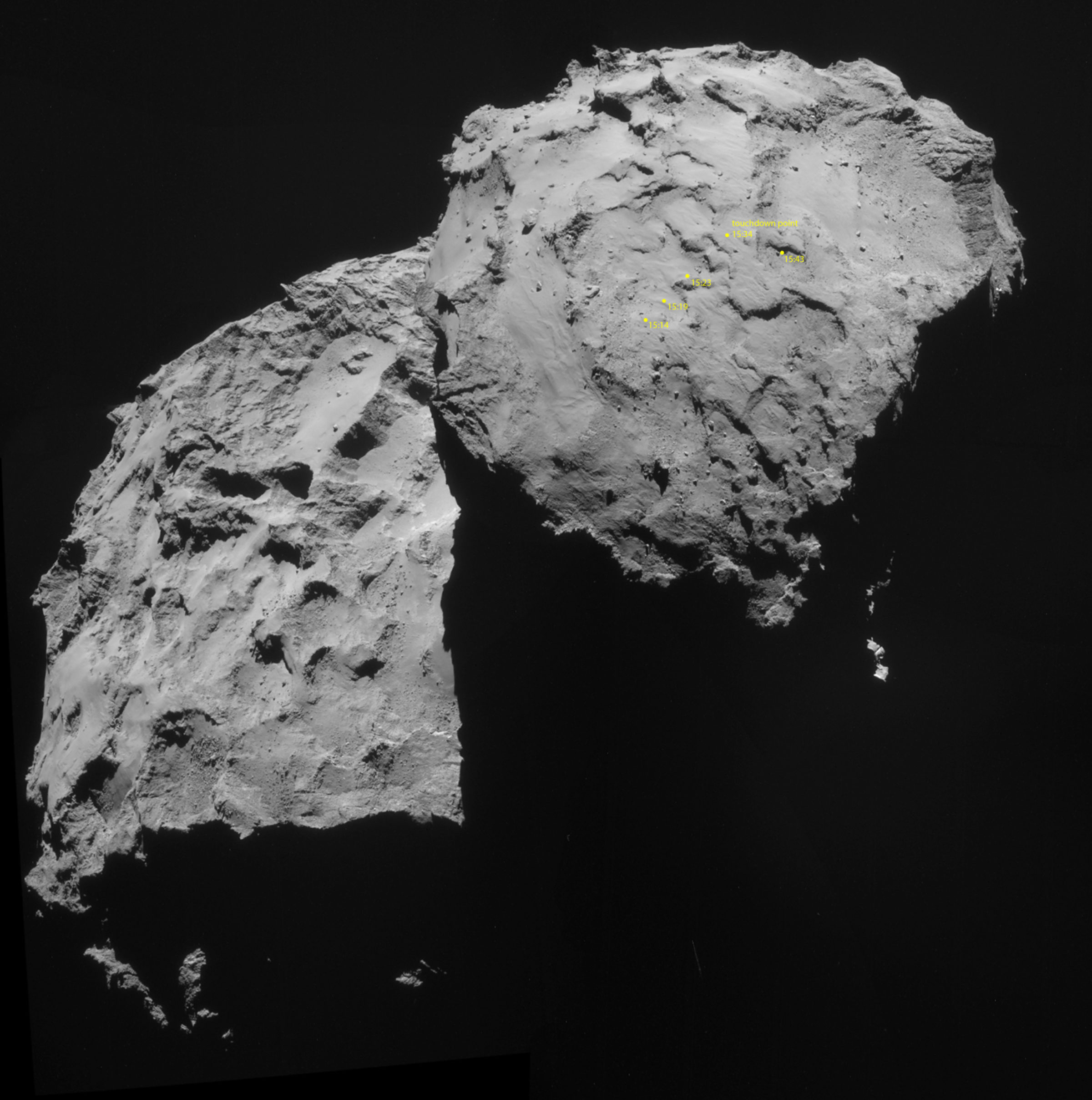

I wanted to get a wider view, so I plotted the spots where we see the descending lander on two context images, both taken September 14, the first by OSIRIS, the second by NavCam:

It's really difficult to imagine what it would have been like to ride on Philae as it climbed and climbed on its high bounce above the surface, drifting eastward over time. We know that its second bounce happened about two hours after the first one, and it was a short bounce, and when it came to rest it was wedged up against a cliff. Where, exactly? Hopefully OSIRIS will figure that out soon -- but the fact that Philae's solar panels only saw light for 1.5 hours per day, the orbiter has to be in the right place in the right time to see the shiny spacecraft sunlit.

Another cool thing about the OSIRIS images is that we can look at changes to the surface of the comet that were caused by the landing. The community at unmannedspaceflight.com has been actively examining these images and trying to understand them. And I have to say that the post-landing changes are quite puzzling, at least to me. You see several circular spots that look like mini-craters, and want to interpret them as footpad locations. But there are too many of them, and at least one of them is too far away from the others for all of them to have been made at the same time. Are any of these footpad locations? Do these spots look circular by some trick of the light, but are actually deposits of darker material on the surface? It's hard to imagine how you darken a comet. It's all kind of confusing; I'll leave you with an animation that shows what I see, but I'll tell you I'm really looking forward to the ESA operations team's interpretation of these photos, because I don't think I'm quite getting it!

Let’s Go Beyond The Horizon

Every success in space exploration is the result of the community of space enthusiasts, like you, who believe it is important. You can help usher in the next great era of space exploration with your gift today.

Donate Today

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth