Emily Lakdawalla • Oct 03, 2012

Curiosity catches sunspots along with Phobos and Deimos transits

Curiosity was commanded to take several sequences of images of Mars' moons Phobos and Deimos passing across the disk of the Sun several times over the last three weeks. The first of these was a grazing transit of the Sun by Phobos on sol 37, and there were more shot on sols 38 and 42. I haven't written about these pictures yet for two reasons. For one, it's taken a while to get enough full-resolution frames down from Mars to assemble a smooth movie. The other reason will take a bit more explaining, as it took me all over the Internet digging up clues.

First things first, though: animations of the transits. There have been several. The sol 37 one was a grazing transit, Phobos' fast-moving shadow taking a little bite out of the Sun in a sequence that lasted only 20 seconds. There are not very many images from this sequence that have made it to Earth -- just a dozen or so -- and the versions that have been posted on the raw images page are gnarly with JPEG compression. There was an officially released version of the photo including nine frames:

Something in that release caught my eye: a little dark dot near the bottom center of the Sun's disk, which seemed to persist from frame to frame. Could that be a sunspot? Spirit and Opportunity have imaged the Sun tens of thousands of times but probably never saw a sunspot, because the resolution of the Pancam was not sufficient (or the sunspots just haven't gotten big enough) to make them out. Curiosity's Mastcam-100 gets many more pixels across the Sun, so it seemed to be a distinct possibility. During the press briefing I asked this question of Mark Lemmon, the atmospheric scientist who has been behind most of Spirit and Opportunity's astronomical imaging, and who seems to be leading that charge on Curiosity as well. He said they didn't know yet; that there wasn't a large enough sunspot group to try.

Well, that definitely wasn't "no." So when the images of transits captured on sol 42 started coming down, I checked again. And I was increasingly convinced I was seeing a sunspot, or even a group of them. Here is an animation of nearly 100 images of Deimos transiting the Sun at about noon local time on sol 42.

Deimos' apparent motion across the sky is far slower than Phobos', so as Curiosity held the camera still to watch the transit, both the Sun and Deimos (mostly the Sun) moved across the sky. To check if I was seeing a sunspot, the first thing to do is to align all the frames. There is a lot of noise (a result of the way that this particular kind of image is processed before being posted to the Internet) but it sure looks like there's one or two sunspots near the center of the image.

A good way to deal with noise in astrophotos is to shoot a lot of images at the same spot and then "stack" them together. Assuming that the noise is random, it should cancel out, and "real" features should be reinforced. The image below is a stack of 30 frames from the animation. Deimos is stretched out into a streak, and there is definitely a dark dot just below the center of the disk. And maybe a second dot adjacent to the obvious one, up and to the right.

I'm pretty convinced, but it was pointed out to me on unmannedspaceflight.com that there are, of course, other spacecraft currently imaging the Sun. Now, if you check the Solar System Simulator for the day that this image sequence was taken (September 18), you'll find that Earth and Mars have quite different points of view on the Sun. Mars is more than 90 degrees, maybe 100 degrees behind Earth. So its view of the Sun on September 18 would've been quite different from ours.

While most of our Sun-pointed spacecraft are on Earth or in Earth orbit or at Lagrange points that follow Earth's orbit, there are two that are not: STEREO-A and -B. Here is where Stereo A and B were on the day of the Deimos transit. (I made the graphic using this handy tool on the STEREO website.) Lo and behold, STEREO-B's point of view on the Sun is extremely close to Mars' -- I eyeball it at only 20 degrees difference.

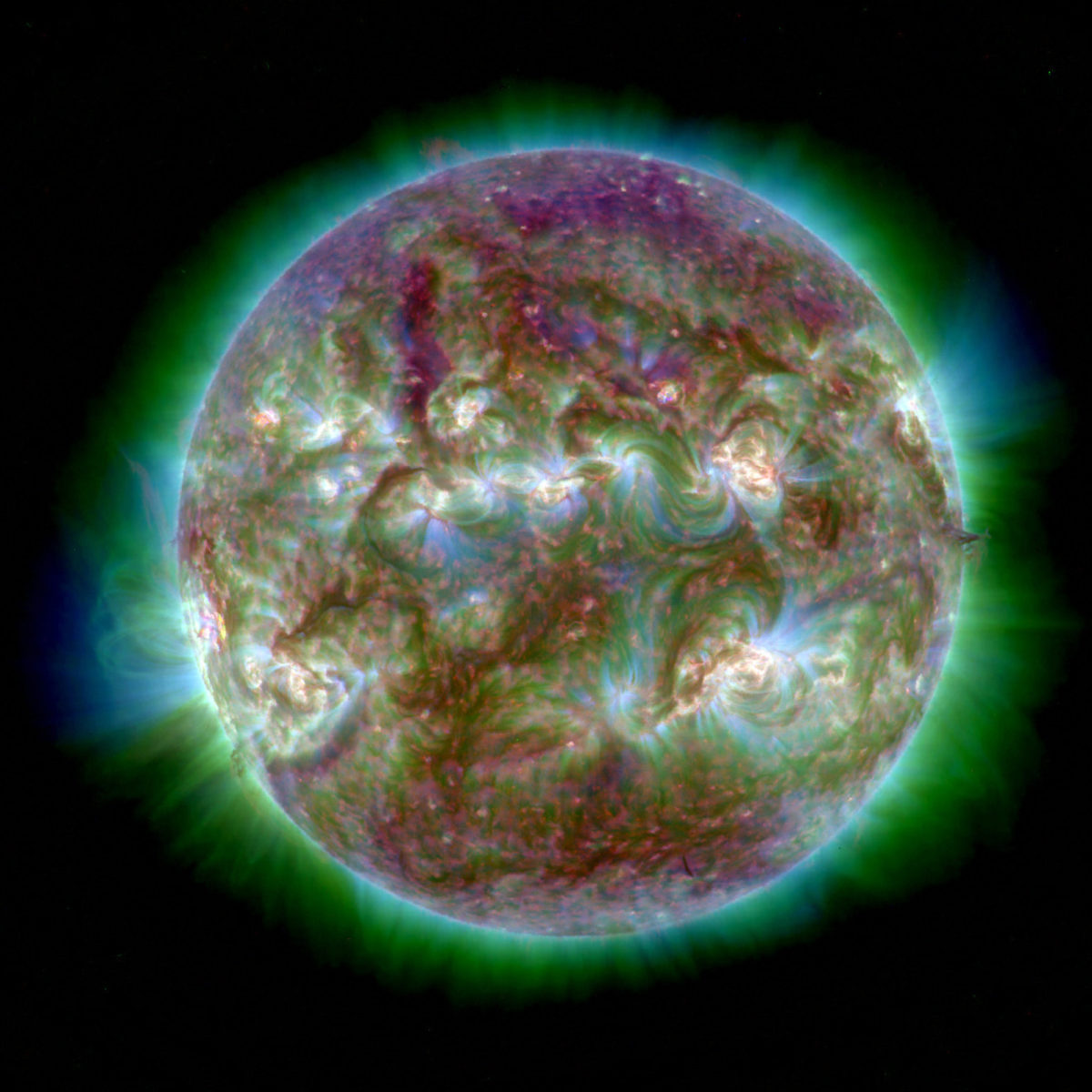

So what did the Sun look like to STEREO B on the day of the Deimos observation? I can answer that question, because NASA's solar missions have been freely sharing their data with the public in near-real-time for years. Just go here and follow the link to the STEREO image search tool. It takes a bit of fiddling with options to find the image I want, but I eventually got to a photo that looks pretty cool and shows some active regions on the Sun.

But there's a surprising amount of activity on the Sun. Are any of these our sunspots? The answer is.....I have no idea. There aren't any images of the Sun from STEREO that directly show sunspots. Clearly there are some active regions on the Sun, but not all of them produce sunspots, and there's no way to determine if my little faint dots actually correlate directly with the patterns seen here. A dead end.

OK, so I had to try a different approach. The Solar Dynamics Observatory produces beautiful images of the Sun in wavelengths where you can see sunspots. It is located in Earth orbit, though, so it doesn't see the same face of the Sun as Mars does right now, at least not at the same time. What's at the center of the disk of the Sun as seen from Mars is currently on the left-hand limb of the Sun as seen from Earth. If Mars is about 100 degrees behind Earth right now, and the Sun rotates at about 14.5 degrees per day (at least at the equator), then whatever was at the center of the disk on September 18 for Mars should have rotated into position just about exactly a week later. So...let's look at those lovely SDO images, starting on September 18 and watching to see if any spot starts near the limb and winds up near the center of the solar disk on September 25. This animation does exactly that, starts September 18, then skips at a frame per second through the next 6 days until it pauses on September 25.

Lo and behold, there is a sunspot that starts at the limb and rotates into the center of the disk. It actually starts out as a triple spot, three dark spots clustered tightly together, but two of the three shrink and disappear by September 25. It also appears to start out having a smaller companion a few degrees to its west, which fragments and disappears over the course of the week. I'm pretty sure that our September 18 Deimos animation is oriented with north roughly to the right, so I might convince myself that I can see that smaller companion spot. But I wouldn't swear to it.

All in all, this wound up taking me a lot longer than I had planned to spend on the Phobos and Deimos animations. But it was a fun trail to walk down!

Let’s Go Beyond The Horizon

Every success in space exploration is the result of the community of space enthusiasts, like you, who believe it is important. You can help usher in the next great era of space exploration with your gift today.

Donate Today

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth