Emily Lakdawalla • Mar 20, 2009

Attack of the dust donuts

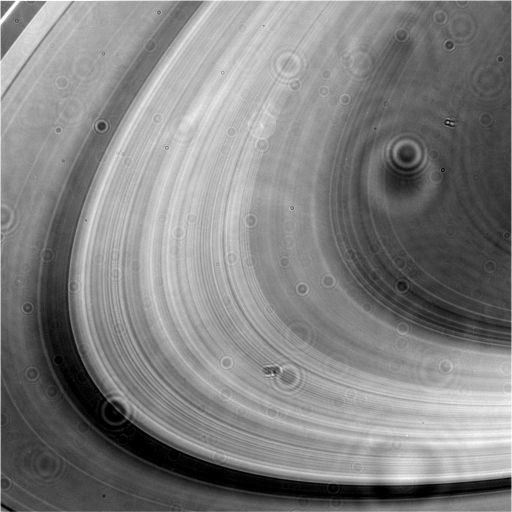

Yesterday I was browsing through the latest raw images from Cassini and came across a set taken of the rings with Cassini's wide-angle camera that all looked something like this:

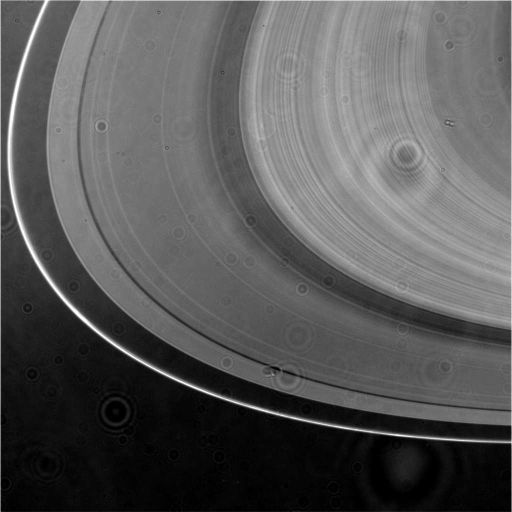

Here's a hint, in the form of another image from the same set.

Each one of those bull's eyes is a single mote of dust somewhere within Cassini's camera system; I'm told that almost without exception, the dust is sitting on the filters that are placed in front of Cassini's optics to capture color information (in these examples, it's the clear filters). Because Cassini's cameras are designed to be in focus on targets thousands of kilometers away, the bits of dust located just centimeters from the detectors are completely out of focus, dissolving into the concentric rings that you see on these photos.

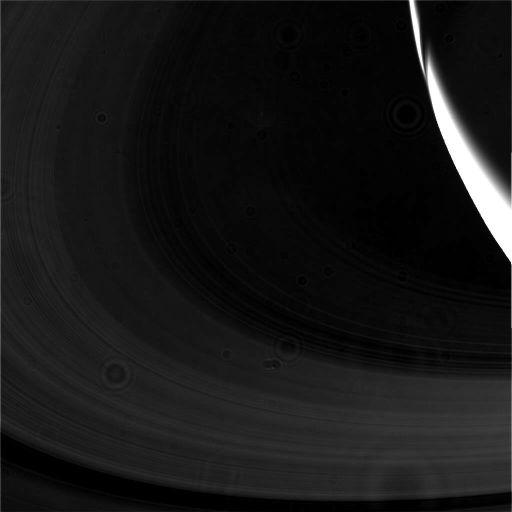

These dust donuts affect every single photo that Cassini takes, but ordinarily they're not noticeable; it's only when Cassini is shooting photos of very dark or low-contrast targets that they become obvious. So I'm accustomed to seeing them in close-up photos of the atmospheres of Titan or Saturn, but I can't recall that I have noticed them in photos of the rings before. (Which isn't to say they weren't there, I just didn't notice them.) For a while I was really, really confused about why they should be so prominent in images of the whole ring system, especially the sunlit face of the ring system, which I think of as a pretty bright target.

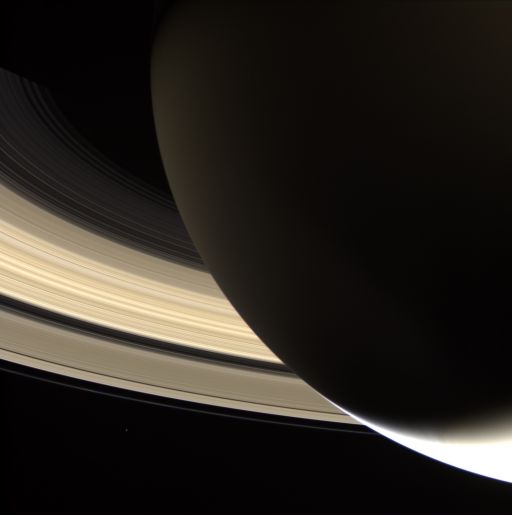

But then I realized something. Saturn's equinox is only a few months away, in August. At equinox, the Sun is going to set from this formerly sunlit face of the rings. But we're so close to the equinox that the Sun must be awfully close to setting, so although we are looking at the sunlit face of the rings, the Sun is coming in from an incredibly low angle, and the rings are getting darker and darker. You can see just how dark they are when you look at another image from this set, in which some of the sunlit portion of Saturn itself is visible. The image also makes it clear that although we're on the sunlit side of the rings, we're seeing them at pretty high phase, with the Sun located nearly in front of the spacecraft, a geometry that also makes the rings appear darker than they would if the Sun were behind the spacecraft.

NASA / JPL / SSI

Saturn's crescent and rings

Cassini took this photo of Saturn's main ring system with its wide-angle camera on March 10, 2009. The spacecraft was on the night side of Saturn, so the planet appears only as a skinny crescent. The image is covered with donut-shaped artifacts caused by motes of dust sitting on the filter wheel in front of the camera.Let’s Go Beyond The Horizon

Every success in space exploration is the result of the community of space enthusiasts, like you, who believe it is important. You can help usher in the next great era of space exploration with your gift today.

Donate Today

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth