Emily Lakdawalla • Apr 30, 2008

Where are all the women?

After I posted yesterday's article about the names of features on Mercury, a reader wrote in to point out that although Mercury's craters may be named for "Deceased artists, musicians, painters, and authors who have made outstanding or fundamental contributions to their field and have been recognized as historically significant figures for more than 50 years," there were remarkably few women's names on the list. How could they not acknowledge, he asked me, the cultural contribution of such women as Emily Dickinson and Jane Austen?

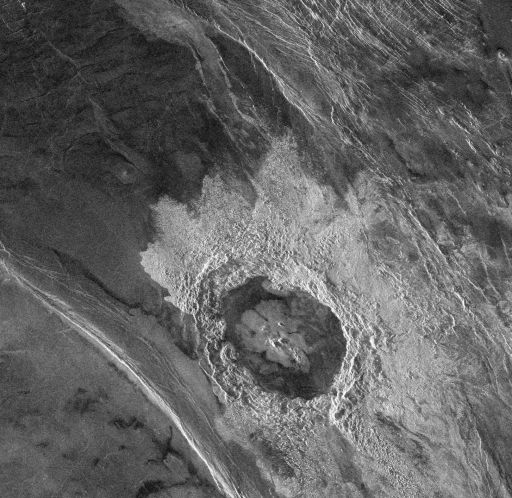

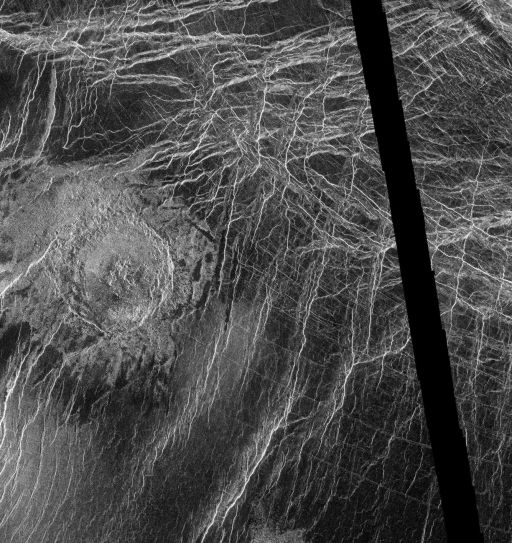

The reason that Dickinson and Austen are nowhere to be found on Mercury is because their names have already been used elsewhere. Venus is an Earth-sized world whose features are, with only three exceptions, named for women, factual and fictional. (The exceptions are three places that were named prior to the space age, from Earth-based radar maps: Maxwell Montes, Alpha Regio, and Beta Regio.) Venus is also where I cut my teeth as a planetary scientist, so it was with great pleasure that I dipped into the Magellan mission archives at the Planetary Data System to hunt down pictures of the craters that have been named for Austen and Dickinson. Perhaps I have a little personal bias here, but I have rarely seen a Venusian crater that fails to thrill me with its aesthetic beauty, wholly independent of its scientific interest. Here is Dickinson, 65 kilometers in diameter, near Venus' north pole, in northern Atalanta Planitia.

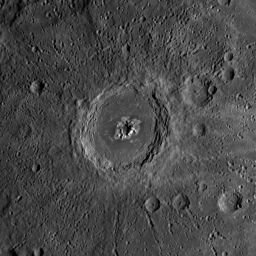

NASA / JHUAPL / CIW

Eminescu crater, Mercury

The 125-kilometer-diameter crater Eminescu on Mercury has terraced walls and a peak ring and is infilled, probably by lava, much like Dickinson crater on Venus. Eminescu is twice the size of Dickinson, but looks similar, because of the lower force of gravity on the surface of Mercury compared to Venus.Here is Austen, 45 kilometers in diameter, in the southern hemisphere, on the northern edge of Artemis Corona:

There are a little under a thousand named craters on Venus, all of them named for "deceased women who have made outstanding or fundamental contributions to their field" if they are over 20 kilometers in diameter or for "common female first names" if under 20 kilometers in diameter. Venusian paterae are also named for "famous women" which I guess opens the door to women who may have been famous but whose "contributions" fall short of "outstanding or fundamental;" though, looking through the list, I don't see that the IAU has been drawing that distinction, as you find such luminaries as Bodicea (queen of the Celts), Sacajawea (guide and translator for the Lewis and Clark expedition), and Sappho (the Greek poet) among Venus' paterae. (Part of the problem here is that sometimes erstwhile craters get reclassified as paterae and vice versa.) Working on Venus, I always loved that it was the planet of women; and it seemed fitting, for a place that was so aesthetically beautiful. (Yes, I consider beauty to be a feminine property. Is this sexist? Maybe. I don't think so, though.)

However, assigning these categories to name features on Venus has had a cost. There is nothing in the "rules" for naming Mercurian craters that requires that they be named for men. However, there is an IAU rule that discourages duplication of names. The fact that Venusian features are named for women, in combination with the excellent images that the Venera and Magellan missions returned of 97 percent of the planet (thus providing a long list of features that required names), has meant that all those names of distinguished women found across Venus are, for the most part, ineligible for use on other worlds. That's why, among Mercury's craters, there are only a few named for important women (these include Brontë, Khansa, Mistral, Sor Juana, and Sveinsdóttir). I believe that by requiring Venusian features to be named for women, the IAU sought to create an opportunity to acknowlege a historically underappreciated group of people, particularly those who may have been slighted during their own time and across history because of their sex, so they fell below the cultural importance standard that was applied elsewhere. And I think they've succeeded in that; mapping Venus has required thousands of names, many of which may not otherwise have been applied to planetary features. But it has had this unintended side effect of drawing female names away from the already-shallow pool that supplies feature names for Mercury, the Moon, and Mars.

I'm not sure that this is a problem that really requires a solution. After all, women are receiving their due, in the features on Venus and across the solar system that are being named for them. However, I do wonder whether it really is confusing to anybody for a crater on Mars and a crater on Venus to have the same name. Usually it's pretty obvious from context which planet you're talking about. The rules were laid out back when all these places were only fuzzily mapped. Now that we have orbiters capable of sub-100-meter resolution on all these worlds, it is becoming a strain to come up with long enough lists of names to cover them all; why not reuse Dickinson and Austen on Mercury?

The IAU already allows reuse of names under some circumstances. Names of feminine goddesses and heriones both factual and fictional were traditionally applied to asteroids, at least in the beginning. And you can find many asteroids whose names are used elsewhere: lots of asteroids share names with outer planet moons (Europa, Io, Dione, and Kalypso/Calypso are just a few examples.) However, there are some names, like Persephone and Cerberus, that the IAU probably wishes they'd not applied to asteroids, and saved instead for trans-Neptunian objects; they do seem to think it would be confusing to have two small bodies with the same name, even if they are in very different places in the solar system.

It's not really the IAU's fault that they couldn't foresee what we'd discover, and reserve lists of names for the as-yet-unseen places. They certainly had no way of foreseeing the stepwise pace of discovery of features on the surfaces of all these different destinations in the solar system. Now that there are so many things out there to name, it might perhaps make some sense to relax the restriction on re-use of names. But if we allow re-use of names of Venusian features on other worlds, then the restriction of female names for Venus does begin to look a bit sexist.

So, this may be a problem without a solution. The world is full of those.

-----

CODA: A Mars researcher has expressed curiosity to me about how many craters on Mars actually are named for women. He didn't have time to examine the list fully, and neither do I; so I've posted the full list of about 1,200 Martian and Mercurian craters, with citations, in Excel format or tab-delimited text format. It's actually not that bad; more than 600 of the Martian craters are named for towns, so there's only about 600 to hunt down. If you'd like to volunteer to gender the list (if I may coin a verb), or some part of it, please send me an email (if you want to do just part, tell me how many you'd like to check and I'll tell you which rows in the table to check, so as to avoid duplication).

Let’s Go Beyond The Horizon

Every success in space exploration is the result of the community of space enthusiasts, like you, who believe it is important. You can help usher in the next great era of space exploration with your gift today.

Donate Today

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth