Emily Lakdawalla • Jan 31, 2008

Ride along with Cassini at Saturn!

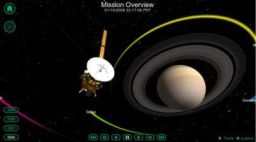

The Cassini project released today a very cool interactive application that allows you to see Cassini in motion as it orbits Saturn and passes among the moons and rings, called the "Cassini at Saturn Interactive Explorer" or CASSIE. Once you've downloaded and installed it you can pick a couple of options to see Cassini move among the moons, either from Cassini's point of view or from a fixed, wide point of view, and then you can use your mouse to pan and zoom around the system as Cassini and the movies CASSIE makes use of actual mission data on the position and orientation of Cassini as well as Saturn's moons, so what you see as you watch the 3D visualization run is an accurate simulation of where Cassini was pointing at any given point in time. It's pretty fun to play with; I highly recommend downloading it. Although it's based on the detailed mission data, the interface is very simple and appropriate for schoolkids to play with.

NASA / JPL

Cassini at Saturn Interactive Explorer (CASSIE)

Using "Cassini at Saturn Interactive Explorer" (CASSIE) you can observe or ride along with the Cassini spacecraft as it explores Saturn and its moons using real mission data.- Saturn's moons all have roughly circular orbits. Each one moves at a constant speed, but the moons closer to Saturn move faster than the moons farther from Saturn.

- Most of the moons orbit in the same plane as the rings. You can see this by tilting the view up or down until you make them all line up in one straight line, all overlapping. Iapetus is the odd man out, with a distant orbit that doesn't line up with the others -- it's inclined by 15 degrees. And Cassini also doesn't line up in the same plane either.

- Cassini's orbit is never circular, it's always elliptical, and sometimes it's closer to Saturn and sometimes it's farther from Saturn. When is it moving fastest, and when is it moving slowest?

- Cassini changes its orbit through gravity-assist flybys of Titan. That means that no matter how large or small its orbit, and which direction it's tilted, Cassini's orbit ALWAYS intersects Titan's orbit, even if Cassini and Titan don't happen to be at the crossing point at the same time.

- But if you turn the view so you are looking right at the place where Cassini's orbit crosses Titan's, sooner or later the two always end up at the same spot at the same time. They don't collide, of course, but Cassini usually is zooming only 1000 kilometers or so from Titan's surface, which is less than 1/5 the diameter of the moon. When one of these encounters happens, take a careful look at what happens to Cassini's orbit. Usually, there's a kink in the orbit, where Titan's gravity changed the speed and direction of Cassini's orbit.

- Watch the orbits evolve for a while, and see how rare it is for Cassini and a moon to be in the same place at the same time. That's why most of Cassini's views of the moons are distant. You'll see it's more common for Cassini to be really close to one of the moons in late 2005 and early 2006, when it was orbiting in the ring plane; but pretty rare at other times. Most close encounters with moons had to be carefully set up using Titan flybys and rocket firings.

- Make sure to check out September 2007, when Cassini made one gargantuan swing out from Saturn to go visit Iapetus.

- For more clues as to what Cassini is looking at, when, make sure to visit my Cassini tour page. To help you navigate, I just added internal links that jump to the start of each calendar year; the same links are available in the CASSIE tool.

- The 2.7-meter-diameter white radio dish is obvious.

- The other big thing you'll immediately notice is the 11-meter-long, gold, triangular-cross-section magnetometer boom, which is basically a long pole that keeps the sensitive magnetometer instrument as far as possible from the magnetic fields generated by the spacecraft itself.

- There's three very skinny antennae, orthogonal to each other, coming out from the same side of the spacecraft as the magnetometer boom; these are part of the Radio and Plasma Wave Science Instrument.

- There's a big ring on one side of the spacecraft: that's where the Huygens probe used to be attached.

- At the opposite end of the spacecraft from the radio dish are the two main thrusters, which are generally only used for really big changes to the orbit (like for orbit insertion); also down there are the three black radioisotope thermal generators.

- Finally, on the side of the spacecraft opposite to the magnetometer boom there are various clusters of science instruments; to get a sense of where the cameras are and where they point, at right is a diagram of the optical remote sensing pallet, which includes the two cameras. The cameras all point in a direction exactly opposite to the direction that the magnetometer boom points.

- Looking now at the visualization, with Cassini in motion, you'll often see Cassini turn so its dish points at the Sun and the spacecraft starts rotating. It's actually pointing the dish at Earth, which you can see as a blue speck near the bright Sun; these periods are when it is communicating with Earth, returning data -- note that Cassini can't usually point its cameras someplace and communicate with Earth at the same time. The rotating doesn't have anything to do with the radio communications; Cassini rotates in order to allow its fields and particles instruments to collect plasma and particles coming in from a variety of directions during the time-consuming communications sessions.

- At other times, Cassini is not rotating, just drifting. Try to tilt the point of view so you are looking straight down the magnetometer boom; odds are you're seeing a nice point of view on Saturn or its rings or moons that the optical remote sensing instruments are checking out.

Let’s Go Beyond The Horizon

Every success in space exploration is the result of the community of space enthusiasts, like you, who believe it is important. You can help usher in the next great era of space exploration with your gift today.

Donate Today

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth