Emily Lakdawalla • Jan 16, 2008

New MESSENGER image release: Mercury at high resolution

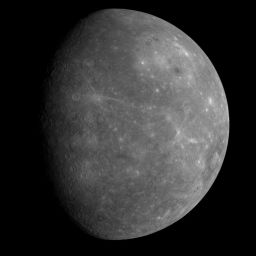

Today's image release from the MESSENGER team is really gorgeous. I'd better go ahead and post it at the top before I start writing volumes:

NASA / JHUAPL / CIW

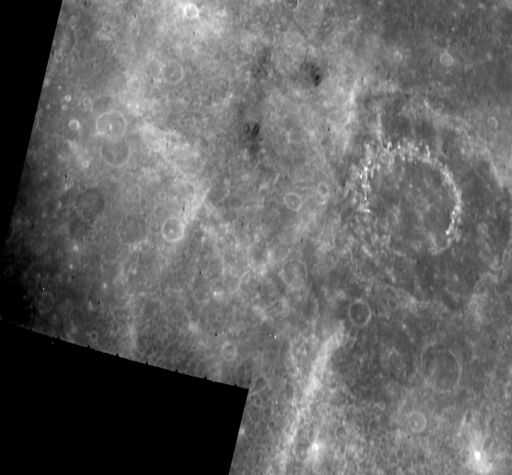

Vivaldi crater and environs from MESSENGER

MESSENGER took this image of Mercury on January 14, 2008 at 18:06, about an hour before the closest approach of its first flyby. The image is one frame from a 55-image mosaic of Mercury's crescent. The most prominent feature in the image is the double-ringed Vivaldi crater and its rays of secondary craters. The outer ring of Vivaldi is about 200 kilometers in diameter. Other craters in the image display a variety of degradation states; some are deep bowls with sharp central peaks, while others are flat-floored, so must have been filled in (most likely by volcanic eruptions).The image geometry is a little unusual, so I'd better explain that before I try to interpret it. Sunlight is coming from the left, and the image covers some areas that are well lit by the Sun, but toward the right side of the image we are getting into the terminator, the day/night boundary on Mercury. By the rightmost edge of the image the Sun slants almost horizontally onto the raised rim of the double-ringed crater Vivaldi, so that the entire floor of Vivaldi is in nighttime darkness, but the peaks of its double rim, especially the inner ring, are brightly side-lit by the Sun. Because MESSENGER had only a crescent-phase view of Mercury at this point, we're looking at the edge of Mercury's globe, so all the craters appear squashed left-to-right from foreshortening.

So what do I see in this image? There's lots of craters, of course, but if you look closely at the craters you can see that there's a lot of differences among them. In particular, my eye is immediately drawn to the fact that the craters at the left side of the image mostly have very flat floors, but among them are a few craters that have fairly pristine bowl shapes and central peaks. When craters first form, they all have bowl shapes, or bowls with central peaks, or peak rings. Craters do not form with smooth, flat floors. So something must have happened -- some geologic activity -- to flatten the floors of all those flat craters; most likely they got filled in by some volcanic eruptions. Those volcanic eruptions had to happen before the central-peak craters, which never got filled in by lava. So already there is a geologic history to tell about this tiny area of Mercury, coming out of this one image.

Another thing that leaps out at me is chains or lines of small craters. You can draw lines through them and they mostly converge at the position of Vivaldi, so that suggests to me that these are secondaries, craters that formed when something big smashed into Mercury to make Vivaldi, which threw mountains of Mercurian crust into the air, which smashed back down to the ground to make a splash of small, secondary craters surrounding the big one.

Another thing I see is subtle linear features running roughly north-south among the smooth plains between the craters on the left side of the image. I spoke with MESSENGER MASCS instrument scientist Noam Izenberg about those today, and asked him if they were wrinkle ridges or rupes or maybe the steep fronts of ancient volcanic flows. He told me they could be all of the above! Hopefully the color data from MESSENGER's other camera will help tease out if they are lava flows; every lava flow has a slightly different composition, and if MESSENGER's science team is lucky, they'll be able to process the color images in such a way that different lava flows with different compositions will leap off the screen in different colors. We'll see.

One thing that the MESSENGER team is pointing out about this image is the fact that although Vivaldi was identified and named based on Mariner 10 images, the topographic depression to the lower left of Vivaldi was nowhere to be seen in the Mariner 10 data. Because there's been a lot of talk about how MESSENGER will be adding to Mariner 10's coverage of Mercury, I thought it would be a valuable exercise to track down the actual, original Mariner 10 images of this same area for comparison.

To track them down, I checked out the United States Geological Survey's shaded relief maps of Mercury, derived from the Mariner 10 data. The USGS maps, which were produced in 1977, are actually artworks, airbrushed paintings based on the original photos. This works well for making planetary maps because images from missions are often taken from many points of view, at different times of day, with lighting coming from all different directions, so to make a map with consistent lighting they really have to draw it from scratch. After looking at the map of the whole planet I figured out that Vivaldi can be found on the Beethoven Quadrangle. The Beethoven Quadrangle map includes a little detail map that shows which actual Mariner 10 images formed the reference points for each area on the map: in this case it seemed the images with numbers 166766, 166767, and 166768 were the ones that contained Vivaldi and environs. Those numbers can be plugged in to the Advanced Image Search tool at the Mariner 10 Image Archive to find the actual images; this archive is great because it contains cleaned-up versions of the images (which originally were marred by lots of noise and reseau markings). Finally, I brought the images into Photoshop, and pasted two of them together that cover the area in the MESSENGER image. The original Mariner 10 images were significantly foreshortened, squashed north to south, so I stretched them vertically to make Vivaldi crater look more round. With this stretching, the Mariner 10 image below has somewhat smilar pixel resolution as the MESSENGER photo above.

The precision of the pointing is even more amazing than I realized. I've been exchanging emails with MESSENGER mission design lead engineer Jim McAdams, who pointed out to me that the last time MESSENGER fired its rockets to fine-tune its trajectory and aim for the 200-kilometer-altitude flyby point was nearly a month before the flyby, on December 19, 2007, when the spacecraft was more than 100 million kilometers away from Mercury. They missed their aimpoint by only 1.43 kilometers in altitude after traveling that 100-million-kilometer distance! This is, in Jim's words, "spectacular" targeting.

They did have a planned opportunity for another rocket firing to take place on January 10, but were able to skip it through an ingenious application of a spacecraft navigation technique that is near and dear to the hearts of Planetary Society members: solar sailing. Jim told me,

We were able to cancel the planned TCM-20 [Trajectory Correction Maneuver number 20] on January 10 by "solar sailing" the spacecraft closer to the intended aimpoint. Analysis performed by our Guidance & Control, Navigation, and Mission Design teams all indicated that TCM-20 could be cancelled if we achieved the needed shift toward the target point by tilting the solar panels an extra 20 degrees away from the Sun about three days earlier than planned.

We have computer models of the spacecraft that link the actual (past) and predicted spacecraft attitude to distance from the Sun, solar flux, and surface reflectance properties for all components of the spacecraft that face the Sun. The net solar radiation pressure acceleration is computed for each of the sunlit components of the spacecraft, and the resultant sum is applied as a trajectory perturbation. These models are frequently updated as more orbit data is collected and analyzed. Accurate computation is very important in Mercury orbit, especially since trajectory correction maneuvers occur in pairs only once per 88 days after Mercury orbit insertion.

Let’s Go Beyond The Horizon

Every success in space exploration is the result of the community of space enthusiasts, like you, who believe it is important. You can help usher in the next great era of space exploration with your gift today.

Donate Today

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth