Jason Davis • Oct 17, 2019

“I Talk to It Every Day”: Students are Vital Members of LightSail 2 Team

It took 10 years to transform The Planetary Society's crowdfunded LightSail 2 mission from an idea on the drawing board into a space mission. Dozens of people worked on the project over the years, backed by funding from more than 50,000 Planetary Society members, private citizens, foundations, and corporate partners.

But out of all those people, only one person, known as the ground operator, can communicate with the spacecraft at a time. That role is often filled by Michael Fernandez, a fourth-year physics undergrad at Cal Poly San Luis Obispo. When he's on duty, you can find Fernandez in the Cal Poly CubeSat Laboratory, also known as PolySat, ready to punch commands into his laptop whenever LightSail 2 is in range of the spindly radio antennas on a nearby roof.

Due to the complexities of orbital mechanics, LightSail 2 is only in range of its ground stations at Cal Poly, Purdue, Georgia Tech, and Kauai Community College for a few minutes each day. During those intervals, it's Fernandez's job to complete any tasks requested by the mission team. He might command the spacecraft to send him some stored telemetry or upload new orbital data that helps LightSail 2 know where it is.

It's not all that different than using a command-line interface to transfer files between computers. Except the computer he's talking to is 700 kilometers overhead, flying at a speed of 7 kilometers per second.

"I think of LightSail 2 as my baby because I talk to it every day," Fernandez said. "In fact, I think I probably have the most intimate connection with it right now, because I'm actually clicking the button."

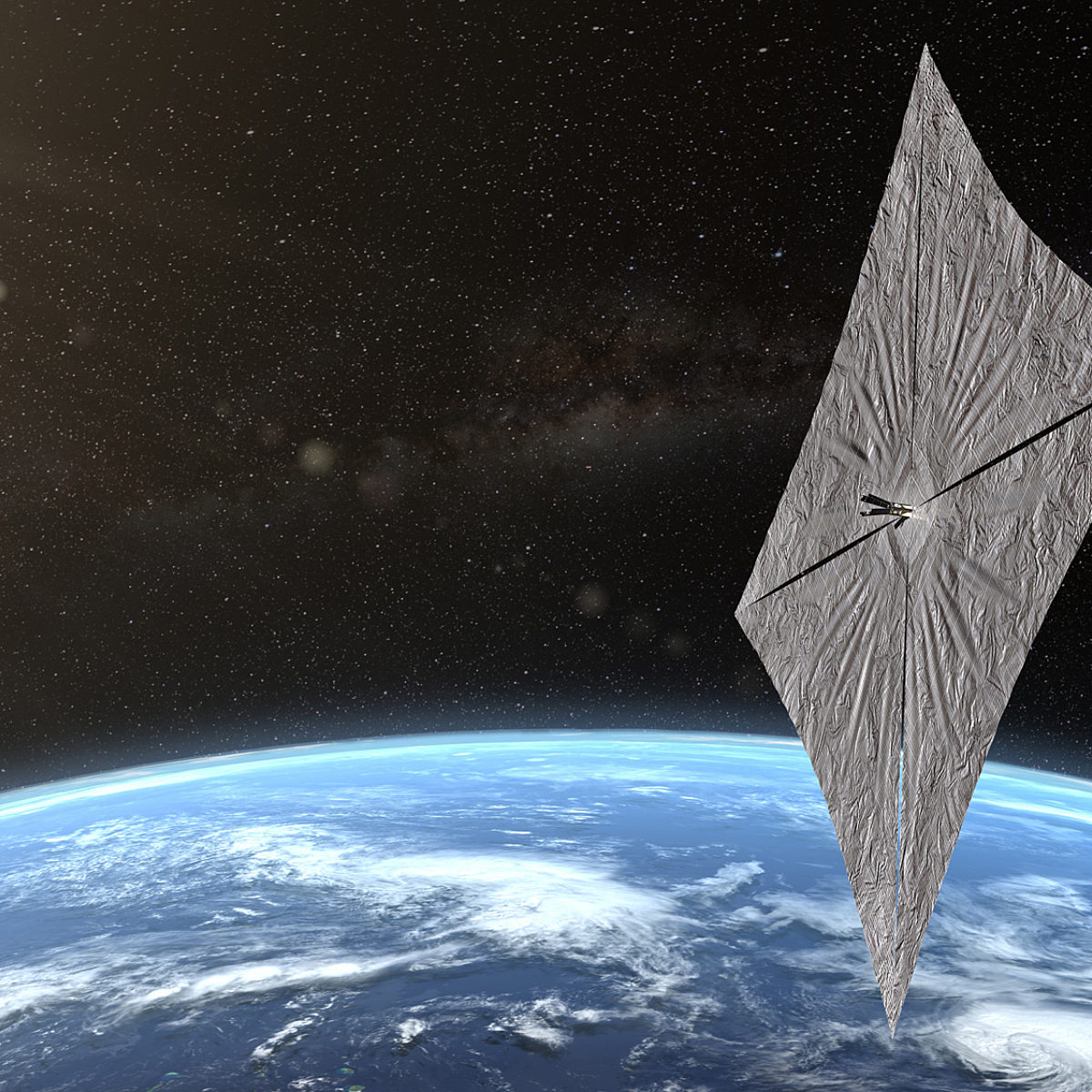

LightSail, a Planetary Society solar sail spacecraft

LightSail is a citizen-funded project from The Planetary Society to send a small spacecraft, propelled solely by sunlight, to Earth orbit.

Students like Fernandez have benefited from the proliferation of CubeSats—small, standardized, low-cost satellites that often hitch rides to space with larger payloads. CubeSats have the same basic needs as any other space mission—things like communications, power, and attitude control—which makes them an ideal way for students to get real-world space mission experience.

"The LightSail 2 mission has done more than just demonstrate a new technology—it has provided valuable training opportunities," said Planetary Society Chief Operating Officer Jennifer Vaughn. "We're excited that our spacecraft is helping to prepare a new generation of scientists and engineers for future missions."

"The student members of the LightSail 2 flight team play a critical role in mission operations," said David Spencer, LightSail 2 project manager. "They do a lot of the heavy lifting of day-to-day operations, and perform key analyses that we rely upon to understand the mission performance."

A Rewarding Experience

Early in the mission, many of LightSail 2's communications passes happened in the middle of the night. Cole Gillespie, a Cal Poly junior working on a bachelor's degree in aerospace engineering, was at the lab when LightSail 2 first phoned home on 2 July 2019. He served as a backup operator for night passes, downloading health data and uploading the commands to prepare LightSail 2 for solar sail deployment. Although Gillespie could control the Cal Poly ground station from his home, he usually came in to the lab, where he could see screens displaying the intensity of the radio signals zipping back and forth with the spacecraft.

"Even if it was like a 2 a.m. pass, I would get up and go to the lab. I felt that not only was it easier for me to run the pass, but also a more rewarding experience," he said.

Gillespie got his start in the PolySat lab by doing his homework there as a freshman. The lab has several missions in progress at any given time, in either design, construction, or operations. Some of the lab's missions are managed entirely by Cal Poly, while others are joint projects with NASA, commercial companies, and institutions like The Planetary Society.

Eventually, people in the PolySat lab started asking Gillespie to help out, and before he knew it, he was in the clean room working on a real spacecraft.

"It was amazing to be able to touch flight hardware as a freshman in college," he said.

Now he's a lab manager. Gillespie said helping out with LightSail 2 gave him a chance to learn more about the operations side of a space mission, and that it was particularly satisfying to see commands he sent to the spacecraft result in pictures of Earth from space.

"I had this picture in my head that it'd be a little more similar to flying an airplane, where commands go up and down in real-time," Gillespie said. "That's not what it's like. You send the command, and you have to make sure it gets accepted by the spacecraft, and then you have to wait for all the bits to come streaming down and collect them to make a full file. It's a little bit slower than what I imagined."

One Problem at a Time

Roughly a week after the Prox-1 spacecraft released LightSail 2, the mission team completed their initial checkout of the attitude control system that would turn LightSail 2's solar sail edge-on and then broadside to the Sun's rays every orbit. A lot of that analysis was performed by Justin Mansell, a Ph.D. candidate in aeronautics and astronautics at Purdue University and a member of project manager Dave Spencer's research group in the Space Flight Projects Laboratory.

Those early tests revealed a number of issues with the spacecraft's ability to determine its orientation in space and rotate using its momentum wheel and torque rods. The team decided to delay sail deployment by two weeks to allow time for troubleshooting, and Mansell worked long hours during that period to get to the bottom of the problems. Ultimately, a final test the day before sail deployment showed LightSail 2's attitude control system was performing as expected.

"Conceptually, the orientation of a spacecraft is a simple thing, but the actual implementation is very complicated," Mansell said. "I learned the importance of being able to really stick it through and just solve one problem at a time."

Mansell's connection to The Planetary Society actually started long before he started working on LightSail 2. He remembers watching Bill Nye the Science Guy at school, and says that for Christmas one year his parents gave him Cosmos, Carl Sagan's legendary TV series.

"I was absolutely transfixed by Cosmos," he said. "Going forward, I knew I wanted to do something that was related to space."

While working toward his undergraduate Physics degree at the University of Calgary, Mansell contributed to a space weather mission called CASSIOPE. At Purdue, his Ph.D. dissertation is on fault detection and diagnosis, software that helps spacecraft autonomously detect and fix problems. His experience with LightSail 2 gave him some valuable experience in troubleshooting spacecraft issues.

"If this mission had just worked perfectly, that would have been great. But it was fulfilling to work through these problems and then have it work at the end," he said.

Worth the Experience

Students who work in the Cal Poly CubeSat Laboratory are expected to volunteer at least 10 hours per week on the lab's projects. Balancing that extra work with a full-time course load can be challenging. Fortunately, the busiest part of the LightSail 2 mission happened in July when classes were not in session.

Now that LightSail 2 has completed its primary goal of demonstrating flight by light, some communications sessions can be scheduled to occur automatically. However, many operations are more efficient with a human at the controls, meaning you'll often find Michael Fernandez on console in the PolySat lab. He usually participates in the team's daily conference calls, providing updates on what tasks were accomplished during the previous days' flyovers.

Fernandez is also working on a deep space CubeSat project for NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Gillespie, meanwhile, expects to spend an extra year at Cal Poly finishing minors in astronomy, computer science, and possibly physics. Mansell is wrapping up his Ph.D. at Purdue, and works on a CubeSat project called SNoOPI (Signals of Opportunity P-band Investigation. All three students say their experience with LightSail 2 has greatly helped them prepare for careers working on space missions.

Whatever missions they end up working on in the future, LightSail 2 is likely to stand out because of one reason—50,000 reasons, actually.

"It's especially rewarding to me that 50,000 people have contributed to the mission, and I've had a hand in making it work," Mansell said. "I've definitely felt a tremendous sense of pride, that together, we've been able to do something that's very cutting-edge."

Let’s Go Beyond The Horizon

Every success in space exploration is the result of the community of space enthusiasts, like you, who believe it is important. You can help usher in the next great era of space exploration with your gift today.

Donate Today

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth